by Allen Rowe

This article is translated from the website of the Bains de Dorres, an unexpectedly rich and varied resource for a hamlet of scarcely 150 souls. Many of us have taken to the hot springs in that charming place without knowing anything of its interesting history during the Second World War. The fashionable contempt in which the French hold the clergy seems to have been completely unjustified in that era, but judge for yourselves.

During the German Occupation, the Health Centre at Escaldes, near the village of Dorres, a kilometer from the Spanish enclave of Llivia, was a discreet and convenient passage-place for the resistance networks commanded by the future Minister of prisoners, refugees and deportees, Henri Frenay.

Abbé Ginoux, the parish priest, worked with the director of the sanatorium to receive messages which, by way of Llivia and Puigcerda, reached Barcelona, then Alger as discreetly as possible.

The priest knew all the paths which led to Llivia and, in his worn and mildewed soutane, often hid letters which, if they had been discovered, would have resulted in his execution.

Braving the many dangers of the forbidden zone, he did not hesitate to accompany in person the fugitives who were entrusted to him.

During the winter of 1943-44, his network was given the job of getting six Canadian airmen across the frontier, crew of a plane shot down in France during a bombing mission. These men, hidden for several days in the sanatorium at Escaldes, wanted to reach Gibraltar.

Wisely, Abbé Ginoux sought to put all the chances on his side, for the Germans took the escape of Allied airmen very seriously.

Family friends in Puigcerda whom he contacted, recommended him to some farmers who had a farm between Enveigt and Puigcerda, known as “The Gelabert Tower” or “ Mas Français”. This property had a particularity which, up til then, had been of great interest to smugglers above all: the buildings and their grounds sat astride the French-Spanish border, a situation which lent itself to all sorts of interesting possibilities.

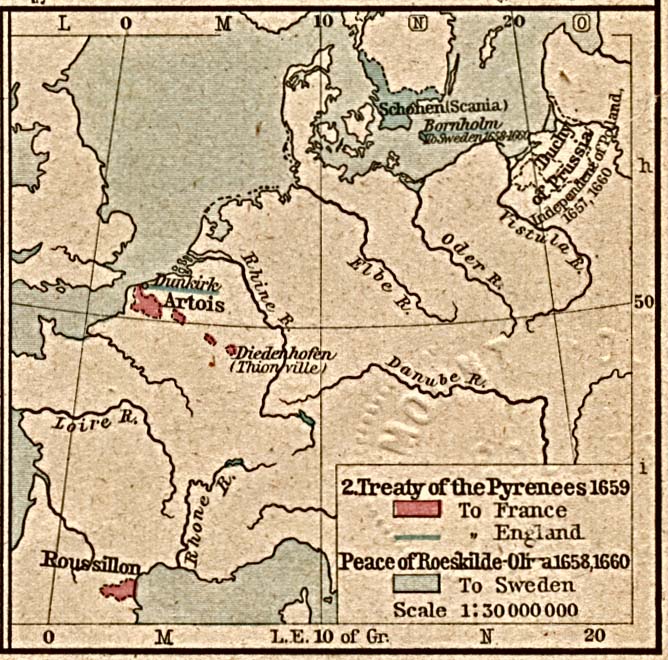

The Resistance happily took advantage of this set-up and the priest of Escaldes must often have blessed the old Treaty of the Pyrenees which, three centuries before, had traced the frontier between France and Spain.

The farmers willingly agreed to give temporary shelter to the Canadians. Their guide then had the job of transforming them into priests, sure that they would have more chance of avoiding arrest if the fliers were disguised as clergymen taking treatment in one of the many rest-houses of the Cerdagne.

The Abbé managed to obtain, not without difficulty, enough soutanes for his plan, too short and only half-hiding the airmen’s’ boots, but they were the best he could find.

To avoid the German patrols from Ur and Bourg-Madame, the little group headed for the Hermitage of Belloch, which overlooked all of the Cerdagne.

As they passed in front of the chapel, our brave Abbé recited a few Our Fathers to seek forgiveness for the venal sin he was committing in thus abusing priestly garments. This prayer clearly attracted divine blessing for, after crossing Route 20 and the track of the Little Yellow Train, all the travellers arrived without any problem at the chosen refuge where reliable friends were waiting for them with warm soup to comfort them after their stressful time.

The greatest danger was now behind them. Our Canadians were able to continue their journey and Abbé Ginoux went back to his parish to send an account of his mission’s success to his superiors.

A rest-house run by monks in the neighbouring village of Angoustrine was another valuable stop for the young people who wanted to cross the Pyrenees. They found food and shelter there and, more importantly, an atmosphere of security which gave them courage.

The Gestapo at Bourg-Madame got wind of the activities of this establishment and arrested several members of the community repeatedly.

Osséja, for its part, provided a group of frontier guides who were both prudent and daring.

This village, situated close to Spain, has a privileged geographical position. Brigadier Lamarques of the Gendarmerie and his men saw the arrival from November 1942, of large numbers of young people and soldiers who wanted to get to North Africa.

The gendarmes advised them of the best places and times to cross the frontier. Sometimes they offered them safe shelter in the rest-houses where they were able to repose for a few hours.

However, little by little, the Germans improved their surveillance, forcing the gendarmes and the guides to be doubly watchful to avoid arrest.

Lamarques was in contact with the leaders of an escape network operating out of Marseilles. The Préfecture of that city prepared identification papers for those who wanted to escape, who were then lodged in the Osséja clinics as if they were receiving treatment. The gendarmes helped them across the frontier in groups of two or three and showed them the best way to reach the Spanish town the furthest from France.

Lamarques was a close friend of the guide Fortuné. He had overheard in a conversation that the German border-guards were watching him and that they were going to interrogate him. Forewarned, Fortuné, was able to answer all questions put to him with no problems. He was only under arrest for a few hours, but it had given him a severe warning. Towards the end of April 1943, he realised that he was no longer useful and fled in his turn to Spain.

More than six hundred people were able to cross the frontier in the Osséja region thanks to the brigade of gendarmes and a little group of devoted guides.

The presbytery of Latour de Carol, home of the Abbé Jacoupy, was a safe house for many. The balcony of the house overlooked two obstacles which had to be overcome; by escapees: the nearby frontier and the Gestapo headquarters thirty metres up from the balcony.

When someone wishing to join the Free French was sent to the Abbé, he would place himself on his balcony and indicate the best shortcut for the nearest Spanish village. From his vantage-point, he could see the German patrols leaving and entering their headquarters. All he had to do then was to choose the time of departure. All this between two masses and two rosaries, with a discreet modesty.

I hope this has given you a glimpse into the reality of life in these idyllic areas we live in; it has never been as easy as now, and was often subject to famine, war and poverty, but the courage of humanity is invincible and showed itself quite brilliantly in those dark days of the occupation.