by Norman Longworth

1939 was a difficult year for France. Not only did it experience the indignity of an invasion on its North East border from Hitler’s hordes late in the year, the country suffered a very different incursion in its far South-West in the early months of the year.

This latter wasn’t a military attack, rather it resulted from the aftermath of the Spanish civil war, when a flood of desperate refugees from Southern Catalonia fleeing from Franco’s bombs and reprisals knocked on the porous gates of the Conflent and its neighbouring regions in the Pyrenees-Orientales.

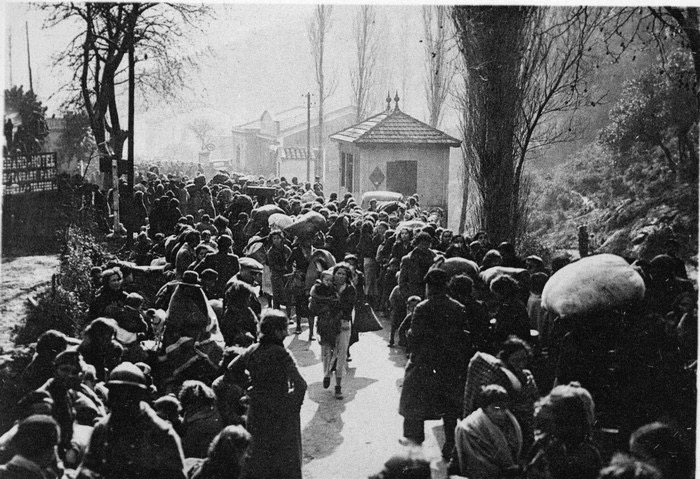

Despite initial French efforts to keep them out, almost half a million people crossed the French border over the Eastern Pyrennees in the depths of winter, suffering incredible hardships, hunger and deprivation on the way.

The Gods of Winter didn’t care to ease their burden. They provided one of the coldest on record.

And so these ill-clothed exiles tramped their way in temperatures of minus 20 degrees up through the snow-filled cols and valleys. Along the coast they came, over the high mountains, along paths later followed in the opposite direction by the fallen airmen seeking refuge from occupied France.

Along the ‘route des aviateurs’ (8000 ft) leading to Mantet in the Conflent, over the Coll d’Ares (5000 feet) to Prats de Mollo in the next valley, through the Cadi mountains (8000 feet) into the Kingdom of the Cerdagne and thence down the Tet valley to the Conflent.

Families with children of all ages, grannies and granddads, exhausted soldiers and civilians, the poor, the destitute and the shattered – all hoping, expecting, that their cultural cousins across the border would recognize their plight and welcome them into their homes. Or at the very least offer them some kind of sanctuary.

Back in what was now Franco’s Spain, many of the men had, for 3 years, fought bravely against the dictator’s well-equipped forces, winning some battles, losing most. Side by side with them, the rag-tag army of the international brigades had made their own history, some of them retiring home to write about their experiences – Laurie Lee, Ernest Hemingway, Jack Jones, George Orwell and many others lesser known.

But Franco had the support of the Fascist dictators, Hitler and Mussolini, and their massive contribution outweighed the occasional backing of the Soviet Union and the studied neutrality of other European nations.

This, together with the constantly bickering factions in the Republican forces, made the difference between victory and defeat.

More often than not, brute force overcomes naïve idealism and hopeful dreams, and when Barcelona became the last Spanish city to fall on January 26th 1939, the cause was lost.

Nor did Franco celebrate his victory gracefully. Determined to stamp out republicanism forever he blitzed the defeated army and its cities with the fervency of a born-again inquisitor. Debilitated by 3 years of unrelenting war and shell-shocked by the Franquiste bombardment hundreds of thousands of republicans, many with their families in tow, sought sanctuary in France.

This was ‘the Retirada,’ the retreat.

The refugees were not welcome in France..

The milk of human kindness seemed to have soured in the Pyrenees Orientales of the time. The France of 1939 was far from being the sister republic that would offer succour and support to its fellow Catalans.

Enfeebled by an economic crisis, and in thrall to rampant xenophobia, similar to that existing in America, The UK and other European countries today, French society offered the refugees a less than enthusiastic reception.

Maybe it was the indifference and disorder of a weak French government that produced this but I doubt it. Half a million is rather a lot of people for a small poverty-stricken department with no industry to take on board without preparation and support. After all, wasn’t 25,000 the maximum number of Syrian refugees for the whole of France in 2015?

What to do with these intrusive fellow Catalans in the less sophisticated world of 1939? The answer was obvious. Declare them to be ‘foreign undesirables’ (a designation passed in the previous year by the national government) so that they could be legally imprisoned, and then put them into concentration camps – show those other invaders later in the year 1939 how it’s done.

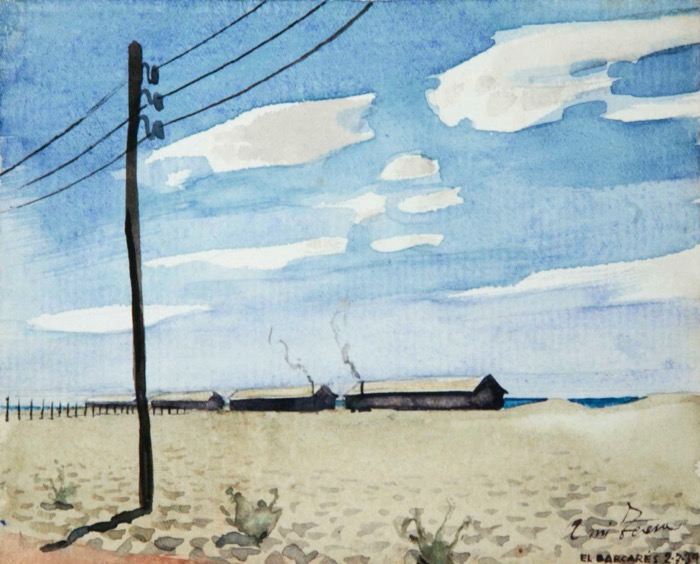

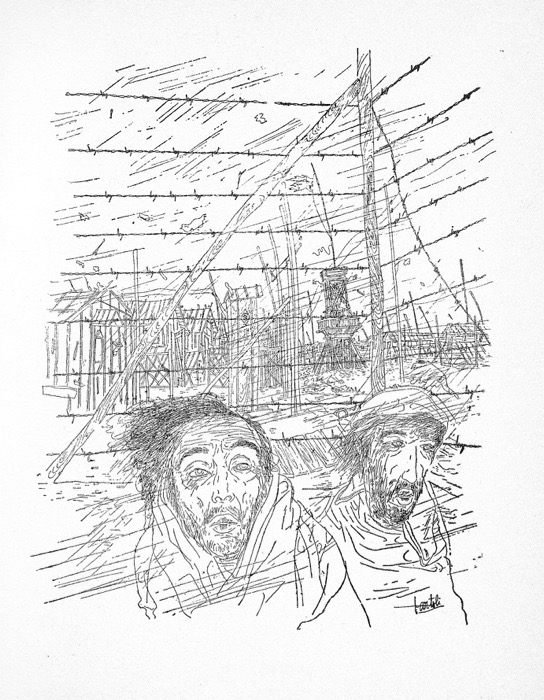

By the first week of March, 87,000 men alone had been incarcerated into what was euphemistically called an internment camp on the beach at Argeles-sur-mer. Here, enclosed by razorwire fences, they endured the ice-cold tramontane whistling down from the frozen mountains, the indignity of prison life and the kind attentions of Senegalese troops with a well-deserved reputation for ruthless violence.

Nor was the cuisine of cordon bleu quality. After all cooking for 87000 by the seaside is a culinary and logistical challenge of Herculean magnitude.

Even in modern times there are restaurants that haven’t solved it. More often than not there was neither food nor water and what there was was barely edible At least in the later concentration camps there were shacks for the inmates and latrines, however primitive. Not here!

No covered accommodation adorned the beach, not even a tent. The only place to sleep and defaecate was a hole in the sand. Dysentery and disease spread like a viral video and took their toll in lives – an estimated 17000 fewer mouths to feed in 5 months.

Those who survived described how the favourite sport of some of the French guards was to beat up dying men. Dante could not have fashioned a more horrific scenario.

As for the women and children, they were better housed in the equally euphemistic ‘accommodation centres.’ At least most of them had a roof over their head and one meal a day. Scant recompense for losing both their dignity and their husbands due to circumstance. Many of them were ‘redistributed’ to other parts of France with little chance of a future reunion.

The undoubted success of this neighbourly venture led the authorities to construct other rat-infested and squalid ‘facilities’ along the beach at St Cyprien and Barcares, slightly improved by leaky roofs and primitive shelter from the elements.

The idea caught on even more with the arrival of the Nazis. Here was a whole new opportunity for inhuman conduct. A source of free labour, places for housing rounded up Jews, Gypsies and other undesirables before dispatching them to the death camps.

Thousands of the exiled ‘undesirables’, having been on the wrong side of political orthodoxy, were exterminated in the Nazi gas chambers, mainly at Mauthausen in Austria. The majority, though, were conscripted into squads of foreign workers, unpaid of course, while others were sent to be further abused in the Foreign Legion.

One of most notorious of these concentration camps, now immortalised as a museum, can be found at Rivesaltes, near to Perpignan airport. Never again it says on the blurb. Some hope!

And yet, and yet, as with all human endeavour there are beacons of honour and light. Most villages in the Conflent have several families with Spanish names. These were the lucky ones, who were taken into the homes of compassionate Catalans and whose descendants eventually settled down to make their own homes there.

Although many returned to Spain, voluntarily or otherwise – often to suffer persecution, prison or death – others, in spite of their inhuman treatment, volunteered to join the French Resistance and contributed as “Guerilleros Espagnols” to the liberation of France in 1944.

In March 1945 the exiles of the retirada were finally granted the official status of Political Refugees., six years too late.

It is estimated that approximately a quarter of the Conflent’s present-day population are descendants of these Spanish refugees, a positive testament to the healing power of time and longer-term planning.

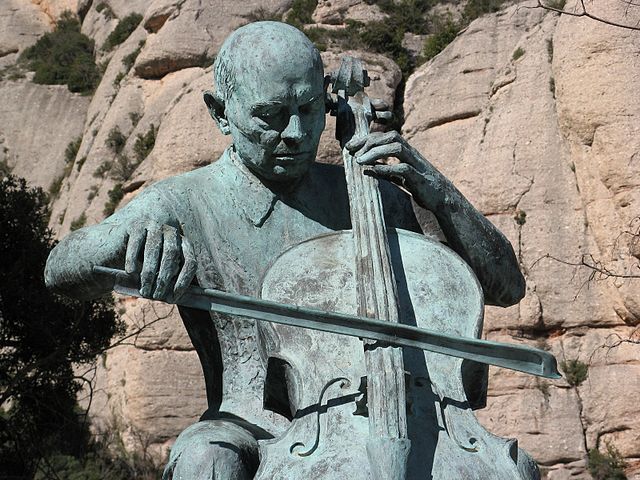

Prades, capital of the Conflent, welcomed Pablo Casals, one of the world’s greatest cellists as a resident, revered and accepted as an honorary Pradeen,

To this day the Festival which bears his name, and takes place every year in July and August, is regarded as one of the foremost chamber music events in the musical world and it has spread its tentacles into more than 20 countries.

Casals vowed that he would never again play the cello while Franco stayed in power. He had a long wait. Franco stayed alive and in power in Spain until 1975, by which time many refugees had become French citizens or had emigrated to Mexico and South America.

Many families were never re-united.

Casals never realised his dream. He died in 1973, but he did play again and taught many young cellists who later became household names as soloists and players in orchestras around the world. The Festival gives Prades, a small town in the Conflent of no more than 6000 people, an international focus and an enduring legacy.

Thus ends this story of one of the major unsung human upheavals of the last century. Maybe there are lessons to be learned from the events of the Retirada for the present day. Or there again, maybe no one is listening. That would be more like human nature.

At that time, I was about 3+, we lived in Perpignan. Maman had a help called Francine who lived with us. When Papa disappeared into a prisoner’s camp in Germany, Maman had to tell Francine that she could no longer pay her wages; Francine chose to stay with for board and lodging.

One day, she took me for a walk, then I remember we were standing on a staircase and Francine told me that her fiancé was in the attic, that we were going to see him and that it was a secret not to be told. Pablo was one of the refugees from Barcelona who had been smuggled out of Argelès camp.

With my mother’s help, they were married and escaped to Mexico.

That day I learnt never to gossip!!!

What a fascinating story Mija. Thank you for sharing.

A moving and thought-provoking comparison between then and now!

For a contemporary account of what it was like in the area, it’s worth reading Helen Legrais’ book about Elisabeth Eidenbenz and La Maternité Suisse d’Elne.

https://www.babelio.com/livres/Legrais-Les-enfants-dElisabeth/141468

Footnote: a correction is perhaps required to Norman Longsworth’s article. Although war was declared in 1939, Germany didn’t invade France until May 1940.

A poignant piece, thank you for sharing.

I’ve been coming to this part of the world for more than two decades and was horrified to discover that the beautiful rugged coastline had such an inglorious past.

I don’t point a finger of blame. None of us can as all our histories and personal experiences harbour tales of intolerance of others.

The Retirada is a story that needs to be told again and again. Least we forget? Many have.

The region is steeped in history and I would recommend visiting the camp at Rivesaltes where the skeletal remains of the accommodation blocks still stand, and at the camp’s centre a magnificent underground museum. The accompanying film footage within proof that history repeats itself as the camp was used after the war to house the Harki of Algeria who had fought alongside the French but then found themselves unwanted after fleeing persecution in Algeria.

I applaud the French who campaigned to keep the camp open as a visitors’ centre. And the several reminders on the beaches and in the town of Argelès where plaques serve as a reminder of past horrors.

Next time you sit on one of the several beaches which had been used as makeshift concentration camps, consider, ‘there but for the grace of God go I’.

Writing the story about my uncle an Australian Bruce Dowding who worked with the PA T line in Perpignan in 1941. He was a liaison person with Ponzan Vidal whose organisation was integral to the operations of the PAT line. I have gathered information about the Retirada and really benefited from reading these posts. It would be my honour if Norman Longworth would contact me directly on my email so that we could perhaps gain some more insight.