by Frank Parkinson

December 21st 2020, when Saturn and Jupiter seemed to be almost touching as seen from Earth, gave rise to great conjecture about the Christmas Star.

You may remember that according to the Gospel of Matthew, wise men saw a “star in the East” which would lead them to the birth place of the Christ child. But if the story is factual, what was the “star”; and could there be an astronomical answer to the question?

Of course the written description of events in the bible may be allegorical or mistaken. But let’s not be too bothered by this and consider what the astronomical possibilities are.

To identify contenders it is necessary to have at least a rough idea of the date of the appearance of the Christmas star.

Matthew says that the Magi spoke to Herod – whose death is given by historians as between 4 BC and 1 BC. Luke says that the birth of Christ was during a census of Judea which took place when Quirinius was governor and therefore could not be before 6 AD. These discrepancies point to a likely birth between 4 BC to 6 AD.

So now we have quite a wide range of dates for our astronomical quest. We do not need to worry too much about the time of year, as it is known that late December was chosen as the date for Christmas for many reasons, not least the Winter solstice and the replacement of various pagan festivals.

So now we can begin to trawl the records to find likely candidates!

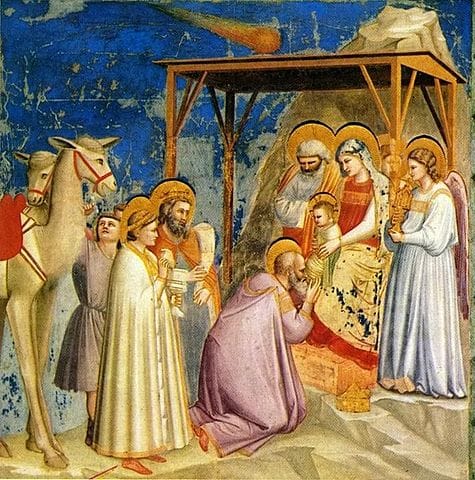

1. Comet

The appearance of a comet visible to the naked eye has always been noteworthy, not just because it is so rare, but also because the object itself, with a tail streaming “behind” (actually pointing away from the sun) is such a strange apparition. In the context of the Christmas “star”, some think that the tail of a comet could have seemed to be pointing at a location on earth – possibly Bethlehem.

So – are there any indications that a comet was visible in the relevant period?

The most famous comet, and one that returns to the solar system every 76 years or so, is of course Halley’s Comet. Incidentally, after Edmond Halley made his prediction that the comet was a regular visitor, it duly returned on Christmas night in 1758, although he did not live to see the proof of his calculations! But for the first Christmas, Halley’s Comet was in our solar system in 12 BC, too early to fit the possible dates.

Of course this does not rule out another comet, many of which are seen only once. The best early records of visible comets were made by the Chinese, and they show that there were sightings of comets in 5 BC and 4 BC. Although the 5 BC comet was reported to be visible for 70 days, there is no other record of either of these two, and so they may not have been spectacular enough to be the Christmas star.

Another possible reason to discount a comet as the Christmas star is that throughout history the appearance of a comet has been considered a portent of disaster, not as a sign of a great and welcome happening.

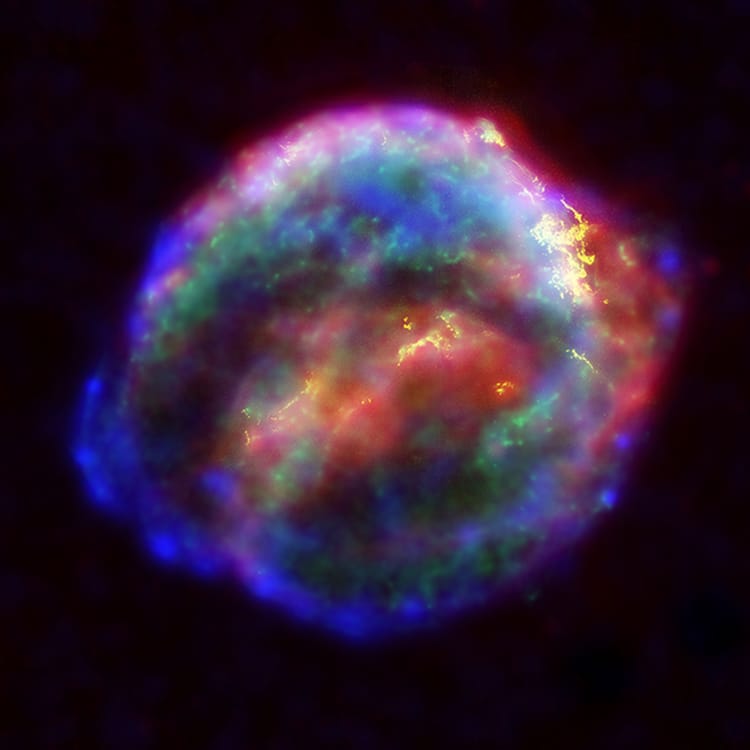

2. Supernova

From time to time, and very rarely, a star is destroyed in a massive thermonuclear explosion which is seen as a brilliant object in the sky for a relatively short time.

The most famous supernova occurred in 1054 and was visible in broad daylight for 23 days – its remains are now the famous Crab nebula in Taurus.

This sort of phenomenon would certainly be noticed by the Magi, and could easily be taken as a sign of a great event about to occur.

Unfortunately for this theory, a supernova would certainly be noticed by many people, not just scholars, and there is no historical mention of such an event at the relevant time. The earliest recorded supernova was in 185 AD.

3. Conjunction

A conjunction is simply the apparent close approach in the sky of two or more astronomical objects such as planets or stars. Conjunctions happen very regularly and so are not usually noticed by anyone except astronomers.

Occasionally however, a conjunction can be noteworthy. Perhaps more than two objects appear close together, or perhaps, as will occur on the evening of December 21st 2020, the conjunction involves major planets – this time Saturn and Jupiter – and their approach is very close indeed.

Very close approaches are called Great Conjunctions, and several such conjunctions occurred in the time period which we are investigating!

In February 6 BC there was a triple conjunction involving Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, but the three planets did not appear to be very close together.

However, during the relevant period there was a very unusual pair of conjunctions between the two brightest of the planets, Venus and Jupiter.

On the early morning of August 12th, 3 BC, Venus and Jupiter appeared close together above the eastern horizon – separated by less than half the disc of a full moon. Eventually Venus would be lost from sight as it circled the sun in its orbit, until 10 months later it appeared in the night sky and had another, even closer, conjunction with Jupiter on the evening of June 17th, 2 BC. Without very good eyesight, perhaps these two brilliant planets appeared to coalesce into a single wondrous object!

You can see a simulation HERE

In summary, you will have seen that it is impossible to be certain about anything related to what we refer to as the Christmas star. This is a mystery that science cannot unravel. Astronomy has taken us as far as it can.

Our personal decision is up to each one of us.

Note: the dates used in this piece are all adjusted to use our modern notation.