The world is HOT enough!

The PO temperature is rising, and records are being smashed. Good news for sun worshippers perhaps, but what may be in store for its landscape, plants and animals?

Too hot for comfort?

Globally, the last four years have been the hottest since 1850, but for over 50 years the whole Pyrenees mountain range has been warming up faster than the world average.

According to the OPCC*, while the rest of the planet has shown a worrying rise of 0.85°C, the temperature in our mountains has increased by 1.2°C! No surprise, then, that 2018 was the hottest year ever recorded in the P-O, averaging 17°C.

Some say the P-O is the sunniest spot in mainland France, but in fact we’re usually around 11th place. There’s no data yet for 2018, but in 2017 Perpignan recorded 2,691 hours of sunshine compared with over 3,000 in the top-ranking Alpes Maritimes.

Wet wet wet?

Not so much! Unsurprisingly, Perpignan is one of the driest towns in France, but the P-O has its moments. Our most recent freak deluge came on 25/11/2011, when eight hours of intense rain on the Albères turned the River Tassio into a destructive torrent through the Vallée Heureuse, Sorède.

Nevertheless, the OPCC says that rainfall across the Pyrenees, while very variable, has lessened (especially in winter and summer) by an average of 2.5% per decade

(1949-2010).

When the wind blows

We often complain about the prevailing north-westerly Tramontane which, they say, blows for 3, 6 or 9 days. It generates spectacular clouds but can be perishing.

One January a few years ago it made daytime temperatures feel like -12°C, and just-ripened lemons froze on the trees and turned black.

What’s surprising is that the tram isn’t our fiercest wind any more. Southerlies are worse.

Let it snow (please!)

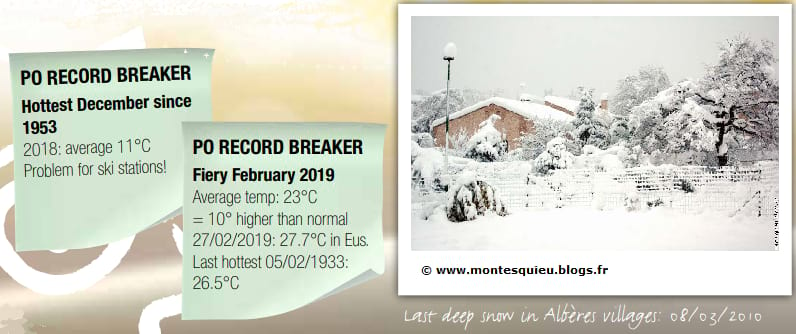

Winters do seem to be warming up and, this year, spring seemed to start in February. While that may be a blip, the OPCC reports that between 1984 and 2016, more than half of the Pyrenean glaciers disappeared, and that the mass of those left continues to shrink, just as the snowline rises.

Over recent decades the number of skiable days (min 30 cm depth snow) has steadily dropped, and the start of the season (with real snow) has slowly been pushed back.

What’s in store?

The OPCC estimates that, depending on how much we reduce emissions etc., the temperature of the whole Pyrenees massif could increase by a further 2 to 7°C between now and 2100.

At that rate, snow depth could halve in the Mid-Pyrenees by as early as 2050. Of course, for skiers we can always create artificial snow. Or can we? To make it, we need water, which may get scarcer. Crop irrigation might get priority.

Tourism could also be adversely affected due to increased dangers of forest fires as well as flash floods and landslips from intense rain.

On a brighter note, progressively warm autumns and mild springs could result in a longer season in the mountains and at the coast, as fewer people tolerate the heat elsewhere.

More importantly, however, less snowmelt and less precipitation, combined with more frequent extreme weather events – from torrential rain to heatwaves – would gradually alter the Pyrenean landscape. Glaciers, lakes and peat bogs, for example, would diminish further. The chemical composition of surface and subterranean water would alter. And all of this would impact mountain flora and fauna.

Time for change

The timing of hibernation, reproduction, egg laying and migration is already changing. Some migrating birds now arrive 10 days earlier than they used to. Amphibians are the most vulnerable vertebrates, and the Pyrenean newt (Calotriton des Pyrénées) is already in decline. A number of butterfly species are flying earlier than normal.

For alpine plants, paradoxically, less snow cover reduces winter insulation and puts them at risk from extreme temperatures.

Some species will adapt but others may disappear entirely. For those dependent on one another for survival – like plants and insect pollinators, predators and prey – if these interactions change, it could have a fundamental impact on mountain eco-systems.

Governments – and each one of us – must take more remedial action now, not only for future human generations but for all living things with which we share this planet.

Sources *OPCC (l’Observatoire des Pyrénées du Changement Climatique) |