L’Homme de Tautavel

JULY 2012 A new human ‘mandible’ (lower jaw bone) from 450,000 years ago has been discovered at the Arago Cave, in Tautavel. This is the 131st discovered human remain to be found at this site. Dated back to around 450,000 years ago, this new human mandible presents anatomical features similar to those previously discovered on the site, with very thick, strong teeth. They help us to better understand the intra-specific populations that occupied the Arago Cave, in Catalonia, over 20 000 generations ago. People who occupied the Arago Cave 450 000 years ago, were hunters of horses, sheep, bison, deer, rhinoceros. They roamed a territory about 30 km radius around the cave. The climate was quite cold and extremely dry, the landscape arid with clumps of trees, crossed by herds of large mammals, swept by a very violent paléotramontane which blew sand into the cave. After preparation, the delicate jaw bone will be put on exhibition from Friday, July 20th. You are invited to attend its rebirth after 450 000 years of sleep in sedimentary deposits of the Arago Cave. |

THE ARAGO CAVE

The actual home of homo erectus was a grotto which these days is accessed from the D9 road to Vingrau, north of Tautavel. Over thousands of millennia, the River Verdouble cut a deep gorge, Le Gouleyrou, forming steep cliffs. The cave – known as La Caune de l’Arago – is cut into the cliff; in prehistoric times, it would have opened out almost onto the river, but now stands high above it, on a rocky overhang.

You cannot actually just walk up and visit the grotto on your Sunday day out. Since 1964 it has been shut off to the roaming public and souvenir hunters to enable painstaking excavations of stone tools and human and animal remains to be carried out; all this under the leadership of the prehistorian Professor Henri de Lumley. Now aged 76, Professor de Lumley has no less than nine decorations and nine science prizes to his name, plus at least 15 publications and 7 films.

The oldest remains found in the grotto are a biface or two-sided stone-cutting tool, 40 cm long, of 600,000 years ago. In 1969 a jaw (pre Neanderthal) of a 40/50-year-old woman was discovered amidst animal remains and tools. Likewise, a year later another jaw of a young man of about 20 was identified.

The oldest remains found in the grotto are a biface or two-sided stone-cutting tool, 40 cm long, of 600,000 years ago. In 1969 a jaw (pre Neanderthal) of a 40/50-year-old woman was discovered amidst animal remains and tools. Likewise, a year later another jaw of a young man of about 20 was identified.

Brief diversion – Neanderthal?

Neanderthal man came after Tautavel man and is so named after a discovery of his remains in the German valley of Neanderthal, near Dusseldorf, in 1856. His appearance was approximately between 230,000 and 29,000 years ago.

At 3.00 p.m. precisely

By far the most interesting discovery in La Caune de l’Arago was made by Professor de Lumley and a group of 30 enthusiasts “at precisely 15 h on 22nd July 1971”. They found the full face and forehead of another man aged about 20, dated 450,000 years ago. Specimen Arago XXI, as this find became in the catalogue, is the oldest fully identifiable and reconstructed face so far discovered in Europe. He was christened Homo erectus tautavelensis to differentiate him from other versions of homo erectus existing in Africa from about 1.8 million years ago.

It is almost impossible for the imagination to leap back to any form of human life so very long ago. If one generation of a family represents a period of 30 years, Tautavel man goes back 15,000 generations! However, such have been the skills of researchers and website designers that with a few clicks of the mouse you can nowadays see it all before you. Here is one of the best sites I have so far found

Sometimes described as fuyant or “shifty” looking, the face of Tautavel man had sunken eyes, large jutting eyebrows and prominent jaws without a chin. He was 1.65 metres tall (5 feet 5 inches) and weighed about 45 to 55 kg. His cranial capacity was inferior to those of Neanderthal man and homo sapiens – a mere 1,100 cubic centimetres. Today the cranial capacity needed to work on computers, pilot aircraft, perform delicate surgery, compose symphonies and write plays is 1,400 cubic centimetres. Homo sapiens emerged in Africa from about 200,000 years ago.

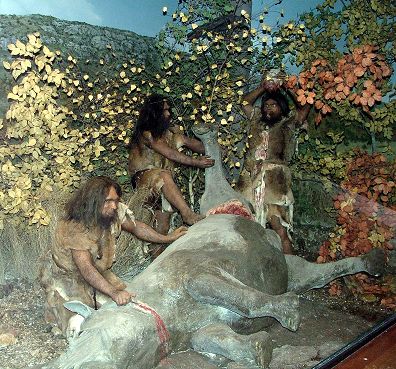

Tautavel man had not discovered how to use fire for cooking and thus ate his meat raw – whether fresh or rotting. With his hunting skills operating within a radius of some 30 km he cannot have gone short of food. Some of his prey, perhaps slaughtered with projectile spears, weighed 700 kilos or more. His diet included reindeer, deer, beef, horse, bison, rhinoceros, mouflon (mountain sheep), thar and chamois. These last two are goat-like mountain animals.

Cannibalism

As evidenced by the presence of cut-up human bones in the grotto, Tautavel man may also have practised cannibalism – though this could have been primarily for ritualistic purposes.

Speech?

The opinions of experts on this aspect are riddled with provisos and caveats. The consensus seems to be that although Tautavel man was incapable of conversation on account of his limited brain size and vocal tract, he may possibly have developed “an early form of symbolic language”, whatever that means. Gestures and crudely vocalised sounds must surely have played a big part in hunting expeditions, not to mention mating rituals.

Arctic Tautavel

The presence of certain animals 550,000 years ago – reindeer, polar foxes, musk oxen etc – indicates an arctic Mediterranean climate “with a glacial wind lashing the steppes at more than 130 kilometres an hour.” La Caune de l’Arago was then in a Mediterranean forest covered with heather and lavender. All a far cry from the usually roasting summers of today!

De Lumley believes that the re-warming of the region began about 8,000 years ago. In his view it will continue over about the next 100,000 years. “The ambient warmth of our climate isn’t about to cool down” he has said. “To put it simply, climate changes every 100,000 years.”

The Museum

Seven years after archaeological work was first begun in earnest on La Caune de l’Arago in 1964, Professor de Lumley initiated the building of the Musée de Préhistoire de Tautavel in which to display to the world the remains found in the grotto. The museum was completed in 1979 and now contains more than 600,000 discovered objects of which 128 are human remains. They are stored in more than 20,000 drawers.

Seven years after archaeological work was first begun in earnest on La Caune de l’Arago in 1964, Professor de Lumley initiated the building of the Musée de Préhistoire de Tautavel in which to display to the world the remains found in the grotto. The museum was completed in 1979 and now contains more than 600,000 discovered objects of which 128 are human remains. They are stored in more than 20,000 drawers.

The remains have not been found on just one level in the grotto; rather on 40 sedimented layers or “floors”, each separated by sterile sand, to a total depth of 11 metres. These separate floors were created by either violent winds or heavy rain in different climactic periods.

A research laboratory was created in 1992, now known as the European centre of prehistoric research, of which the Professor is president. The word European is pertinent because work is carried out on prehistoric specimens from all over Europe, and indeed from anywhere else in the world.

In the top ten

Little wonder that the museum, with its 22 exhibition rooms, is amongst the ten most popular heritage sites visited in the Languedoc-Roussillon. You can read all about the museum on its superbly organised website. Amazingly, in summer, you can even follow by means of video link the work being done in the grotto.

Money and politics

Currently the museum is financed in varying degrees by the state (paying the salaries of 12 employees), the Languedoc-Roussillon région, the Conseil Général of the P.-O, and the commune of Tautavel.

Squandering

There is currently some cause for alarm since a bureaucratic change in the funding of the museum has been mooted, much to Professor de Lumley’s distress. In his opinion the proposed designation of the museum, in an “interministerial report”, as an EPCC (Établissement public à caractère culturel) would mean closure, and “squander” more than 40 years work.

Watch this space! The closure of the site would be a calamity, not least for jobs in the town of Tautavel as well as in the more rarefied world of archaeology. The museum and research centre have directly generated employment in 8 restaurants, 2 hotels, a holiday centre, arts and crafts shops, and several privately owned wine Domaines.

Let Professor de Lumley have his final philosophical words. “To wander through the laboratory of the centre is in some measure to take stock of what we amount to in the face of eternity. Nothing of importance.”