With special thanks to PR

READ ABOUT…..THE PAT LINE

READ ABOUT…THE COMET LINE

The war is nearing it’s end. The Germans occupying France are on edge and expecting the Allied Invasion at any time.

The two main escape routes have been closed down through a combination of clever espionage, and carelessness on the part of both allies and traitors.

Incredibly some safe houses are betrayed by well meaning but careless escapees writing letters via the Red Cross to thank them for helping out.

There are still large numbers of Escapers and Evaders on the run in mainland Europe and it is getting increasingly dangerous for them and their aides. London needs to act quickly and decisively to find some way of hiding those stranded behind enemy lines.

An active member of the Comet Line, Jean de Blommaert, went to London to discuss a new plan of action.

An active member of the Comet Line, Jean de Blommaert, went to London to discuss a new plan of action.

Blommaert was a Belgian who joined the resistance from the moment the Germans invaded his country. He was a real thorn in the side of the occupying German army and had so many assumed names the Germans called him The Fox.

Between them they came up with a series of relays that would eventually get people out by way of Brittany.

A few attempts were made but the vast majority proved fruitless and were just endangering the lives of the allies and the resistance workers.

The plan was aborted in May 1945 when Lucien Broussa, a Sqaudron Leader in the Belgian section of the RAF arrived at the resistance HQ in Paris with new but exciting orders from London. They just read, “Invasion is not far away, DO NOT evacuate any more airmen. Hide them on the spot”

This created a major logistical headache for Blommaert. He needed all resistance members ready for action, he certainly didn’t want them bogged down hiding allied airmen or escaped POWs. It would also increase the chances of his members being caught through careless errors or found out in spot checks or even betrayed.

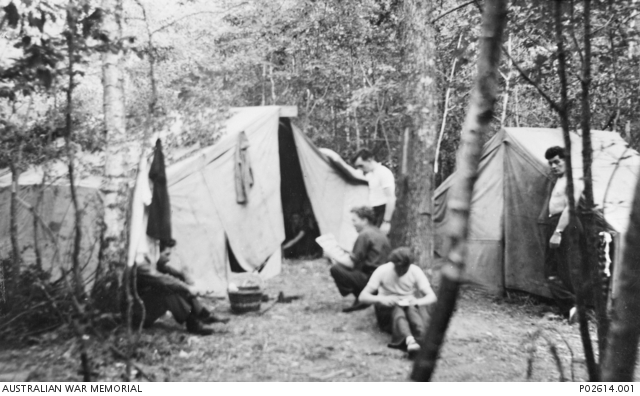

The only alternative he could come up with was to form some kind of big hideaway or a camp where escapers and evaders could sit out the rest of the war and wait to be liberated.

It was a risk to put everyone in one place, but one they had to take as it was preferable to the resistance being caught out at this late stage and stopping any help they could give on the days up to and after the imminent invasion.

The Freteval Forest, 299 square miles of woodland 100 miles south of Paris was chosen. It was chosen for a number of reasons.

Although the resistance was strong in the area they had been inactive so the Germans were quite relaxed and this reduced the danger of searches.

The area was surrounded by lots of farms, handy for food and there were many clearings and plains which were ideal for parachute drops of supplies.

It was also reasoned, (and a massive gamble), that because the area also contained German ammunition dumps, locals would keep away and the camp could be kept relatively secret.

In fact the camp members spent much of their time there so close to the Germans, they were in earshot.

Organising the ‘parcels’ from the north of France to Paris was done by the Head of Resistance, Phillipe D’Albert Lake, codenamed Paul and his American wife Virginia.

They interrogated everybody and hid them temporarily in Paris with the help of Rene Melison who had an apartment just a two minute walk from the Eiffel Tower at 8 Rue de Montessoy.

Living at the top of six flights of stairs and after one unsuccessful search of her apartment the Germans never bothered again.

René made identification cards and taught the parcels French in her lounge. She was also one of the many escorts who would walk in front of the escapers and lead them to the station at Austerlitz. After buying the tickets she would innocently brush past the men and give them the tickets.

The escorts would stay in the same carriage as their parcels. René made over forty trips and the operation was so successful that every single parcel was delivered safely to the forest.

Unfortunately Virginia did end up in Nazi custody. She was riding a bicycle in front of a farm cart carrying a small group of men on the road to Chateaudun. Luckily the cart driver saw what was happening and made the escapers run across a field to relative safety.

A German spotted her accent and realized she was American and although her papers were correct and in order she was arrested. The rest of Virginia’s war was spent in concentration camps including the infamous Ravensbruck where she nearly starved to death.

She withered down from 130lbs to just 54 when she was freed at the end of the war.

The pure fact that 150 men, British, Americans, Canadians, South Africans, New Zealanders, Belgians and even Russians were safely ferried to the forest is incredible in itself but how they stayed undetected so close to so many Germans and so near to so many patrols is nothing short of miraculous.

There were two major rules in the camp. No one was to make a break and they had to respect a code of silence in the camp at all times.

The camp had a system of whistles to warn of the arrival of new recruits and by mid June there was an almost constant flow of new faces.

Whatever the dangers, the camp members did not just sit out the war in the quiet of their new surroundings. They would regularly raid the ammunition dumps, sometimes with the help of a policeman from the local village of Cloyes, Omer Jobalt.

They soon worked out that the patrols would pass by every fifteen minutes, enough time to liberate grenades and ammunition, much of it captured from the British and Americans supplies. The goods would be left in bushes ready for the resistance to collect. In return the resistance would help the men by collecting food locally as well as delivering animals to the camp.

Bread was supplied daily by a boulangerie in nearby Fontaine Raoul. Cigarettes were a problem and were important for morale purposes so raiding parties were arranged to steal them from stores in Cloyes and Chatres. Remarkably store owners were later paid by “anonymous” donations. There was even weekly visits by Msr Barillet a barber from Cloyes.

The camp was so well organized they even had a radio set up on June 14. The receiver was kept in the camp but the transmitter was mobile so as to avoid detection.

Comet Line, Forest paths were given the names of London thoroughfares including Hyde Park Corner which was a point where most of the paths crossed. Here there was a tree used as a notice board, bearing lots of personal messages received on the radio set.

The code that was of most interest was “La Tour Eiffel penche a droite” (The Eiffel Tower leans to the right). This meant a parachute drop of supplies of food, clothes, medicines and money was coming that night. After a drop the men would go out and brush the grass back up so there was no obvious sign of activity overnight in the area.

Camp member William Brayley is quoted from his diary as saying, “It was unbelievable that with all the German patrols scouring the area it was possible for 150 men to gather in the forest, operating a radio to London and spend hours playing golf”

Then the local resistance made a near fatal mistake on the night of 18 July by not covering up evidence of a drop meant for them. The Germans raided Freteval and began a reign of terror locally. Although they had no idea what was actually going on under their noses, they knew something was happening. They would often just strafe the bushes for no apparent reason, luckily never causing any casualties.

By early August it was clear the liberation was closing in, and, on learning the allied front was as close as Le Mans, just 70km away, Colonel Boussa decided to go and try to persuade the allies to rescue the campers quickly.

He was driven there in Msr Viron’s car. They passed thousands of dispirited and retreating German soldiers without a problem before meeting American soldiers to the East of Le Mans.

Coincidentally, Broussa met Airey Neave here. He had left Neave in London just a few months earlier and Neave was there trying to muster a special force to mount a rescue at Freteval. A decision was made for a mission using American troops under British command to go and liberate the camp on 13 August.

Yet another remarkable twist in this event is that the rescuers crossed the front line and grouped up in the local villages of Busloup and Saint Jean Froidmental on August 12. Retreating German soldiers passed by without giving any problems, seemingly not noticing the presence of enemy troops.

The next day the camp members were surprised to be woken by young men speaking English. Flags were soon unfurled and to celebrate liberation, villagers dug out their carefully hidden bottles of finest wines they had stored for this very moment. Resistance members returned one final time to say a fond farewell to the men of the camp.

Why this incredible “Tour de Force” has never been made into a film or is more widely known is a mystery to me. But how 150 men could live so close to constantly patrolling enemy forces for four months is inexplicable and arguably one of the 2nd world wars most amazing stories.

|

What became of the main players in this incredible chapter? Every one of the campers returned to active service again, flying. Thirty eight of them were to die in operations over Germany. Colonel Lucien Boussa returned to England to recruit more Belgians to join the RAF. He was promoted to Wing Commander and awarded the Military Cross and a DFC. The French also honoured him with a French Legion of Honour award. He died in 1967 aged 59. Virigina D’Albert Lake started an antiques business with her husband in Cancaval, Brittany after the war and was awarded the highest civilian medal in France the Legion D’honneur in 1989. She died age 87 in September 1997 and was buried in the American section of the cemetery in Dinan. Her son, Patrick lives close to where she operated in Paris. Despite research, I have been unable to find any information on Phillippe D’Albert Lake or Jean Blommaert. I am sure it is out there so if anyone knows what they did after the war I would be interested to hear. |

Hey! Great text and anecdotes, Jean de Blommaert was my grandfather, I may be able to connect some dots for you…

If you read down to the end of this article there is a snippet or two about the post-war years. Phillipe moved to Brittany with his wife, Virginia, and is buried in Dinard cemetery

https://www.francetoday.com/learn/history/an-american-heroine/