The maquis was one of various forms of Resistance in France’s fight against the German Occupation and the Vichy regime during the Second World War.

In general, it was made up of young men escaping the compulsory labour service in Germany (Service du travail obligatoire or STO) introduced at the end of 1942.

Almost immediately after this law was passed, thousands of young men, especially in the south, fled to the countryside, living in camps in the mountains and garrigues that covered much of the area. They called themselves the Maquis or maquisards, loosely translated as thicket or scrubland.

They were made up of all sorts: the strong, brave, cleft chinned patriots of the movies, who believed passionately in the cause, and those who simply didn’t want to be shipped out to work for the Germans.

Lack of organisation, weapons and military leadership meant that they were ill equipped to go up against the well armed and ordered German army. However, as the war progressed, the British started to include them in their plans and offered them financial and logistical assistance, air-dropping weapons, ammunition, explosives and even professionals to train them in guerrilla warfare.

Differences in political allegiances, and personality clashes amongst group leaders often caused clashes, rivalry and bad feeling between different groups. However, this didn’t stop them from ultimately playing a vital role in preparing the ground for the allied invasion through sabotage of bridges and railway lines, information gathering, and direct attacks on strategic targets.

For many escapees and evaders, Perpignan was one of the final stepping stones to freedom. It was also often the start of a difficult journey, across treacherous, snow topped mountains, dodging German patrols. Resistance groups and escape committees provided guides at great risk to themselves.

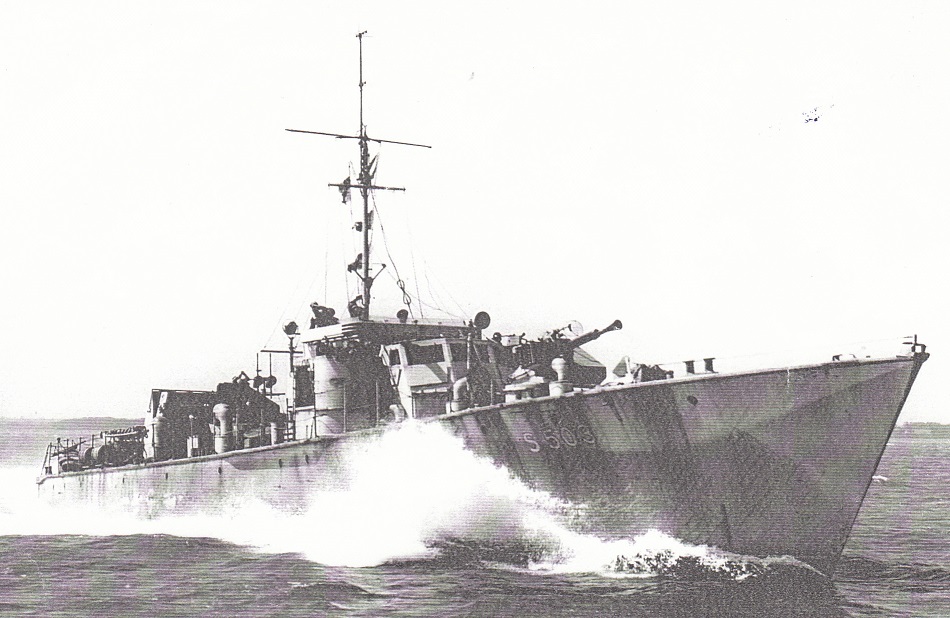

Perpignan’s position close to the coast also meant that British navy vessels could come in close to shore at Argelès-sur-Mer, Canet, Banyuls-sur-Mer and Cerbère and evaders and refugees had the chance of directly reaching Gibraltar by sea, avoiding the risk of being interned by the Spanish.

One such vessel, H.M.S. Fidelity, was assigned the landing of two agents at Canet-Plage to set up a two-way escape line over the Pyrenees. Their mission was also to collect twelve escaping Polish Air Force officers at Collioure.

In fact, the Polish Air crew did not turn up at the rendezvous point, and the rescue crew, disguised as local fishermen, were challenged by a local customs officer and taken prisoner. Their leader, Fidelity’s second-in-command, Patrick Albert O’Leary, managed to escape and ended up staying on in France to help in the setting up of the successful escape and evasion route, the Pat Line.

One of the largest and most successful sea escapes organised by the Pat line ‘Operation Rosalind’, took place in 1941 at Canet-Plage, when forty escapees waded into the sea, to be picked up and taken to the safety of Gibraltar.

In 1964 ‘Pat O’Leary’ was the star of Eamonn Andrew’s BBC television show “This is Your Life”.

Yorkshireman, Geoffrey Robinson, one of the escapees from Canet, described how the 40 escapees waited for a week with Pat O’Leary, wading into the sea every night in vain, until O’Leary radioed London with the message “Pas plus de bateau que de beurre au cul!” (There’s no more a boat here than butter on my arse!)

The rather rude message produced results and they were picked up 2 nights later.

At the end of 1942 the Germans took over the unoccupied zone of France. Sea escapes had to stop and more evaders were obliged to escape across the Pyrenees.

NANCY WAKE – THE WHITE MOUSE

Feisty New Zealand born Nancy Wake (1912 – 2011) led the Germans a merry dance as a major player in the French resistance and Special Operations Executive (SOE) of WW2. Her nickname of ‘White Mouse’, bestowed on her by the Gestapo due to her ability to evade arrest, says it all. Even a reward of 5-million-francs offered by the Gestapo for her capture couldn’t pin her down.

Nurse, then journalist, Nancy’s life changed before war was declared when she interviewed Adolf Hitler in 1933, attended his mass rallies in Berlin and witnessed the random and brutal beating of Jews on the streets in Germany.

She swore there and then to do everything she could to stop it, saying that her “hatred of the Nazis was very, very deep.”

Enjoying the good life in Marseilles with her French industrialist husband, Henri Fiocca, when the war broke out, she immediately volunteered and trained as an ambulance driver, and quickly became a courier for the Pat O’Leary escape line, helping Allied airmen evade capture by crossing over the Pyrenees to the relative safety of Spain. Her husband Henri was captured, tortured and executed.

Nancy Wake Fiocca was one of the Pat Line’s best known agents. As well as delivering her ‘parcels’ (evaders) from Nice, Nimes, Toulon, Cannes and Marseille onwards to Perpignan and the Pyrenees border areas, she also delivered civilian clothing, documents and money, often financed by her husband.

Escorting some Allied airmen from Toulouse to Perpignan in 1943 with O’Leary, they were given advance warning by a railway official that the Germans had set up a checkpoint ahead and would be checking all the compartments. They jumped out of the train through the window and escaped, despite being peppered with machine gun fire.

After two days hiding out, they made their way on foot to Canet-Plage, and the safety of a rescue boat but the incident served to prove that there was a mole in the network, passing information to the Germans. This same traitor, Roger Le Neveu, was to later lead to the arrest of O’Leary by the Gestapo, along with many members of the Pat Line.

Intensely loyal to Great Britain and France, Nancy was feisty, confident, tough and brave and never backed down from a dangerous mission.

Inevitably, she was picked up and interrogated several times, but always managed to escape. Eventually, she crossed the Pyrenees and returned to London in 1943 where she joined the SOE for a return to operations in France after rigorous training in silent killing, explosives, map reading, her mission to work with and coordinate the Maquis, in the lead up to D-Day.

She quickly proved herself in the Auvergne, leading and taking part in ambushes, and sabotage, and it was said that no other sector in the whole of France caused the Germans so much trouble. Her careful advance planning of all Maquis actions saved many lives.

Nancy Grace Augusta Wake died on 07 August 2011 aged 98. According to her wishes, the service finished with her chosen music ‘Non, je ne regrette rien’.

Quote from people who worked with Nancy in the resistance

‘Very feminine, but as tough as any man.’

‘The most feminine woman I know until the fighting starts, then she is like five men.’

‘I do not know what effect Nancy had on the Germans, but by God she frightened me!

What a girl!! Wish that was me, way back then.