Have you visited the Mémorial du Camp de Rivesaltes yet?

Camp Joffre opened in 1938 and closed in 1970. Its history is horrific. In that first year it changed in the blink of an eye from housing for the troops to housing for “Undesirables”. Soon refugees from the Spanish Civil War, Jews and Gipsies joined the “Undesirables”. So handy for the railway. Destination: Auschwitz, via Drancy.

After the signing of the armistice, France was split into two and the « zone libre » in which the Pyrenees-Orientales was included, came under the administration of the Vichy government, a close ally of Germany.

In January 1941, the Vichy regime opened the ‘Centre d’Hébergement de Rivesaltes’ (Rivesaltes Accommodation Centre) on the camp premises for interning ‘Sinti and Roma’, (Gypsies) political opponents and Jews. It was at this point that the sad and sinister history of the camp Joffre began to unfold.

With a capacity of 8000, it was not long before the camp was overcrowded, families were separated, and conditions deteriorated enormously. In fact, Due to the length of time it operated and given the number of people who were interned, imprisoned or confined there, Rivesaltes is now considered the largest internment camp in Western Europe.

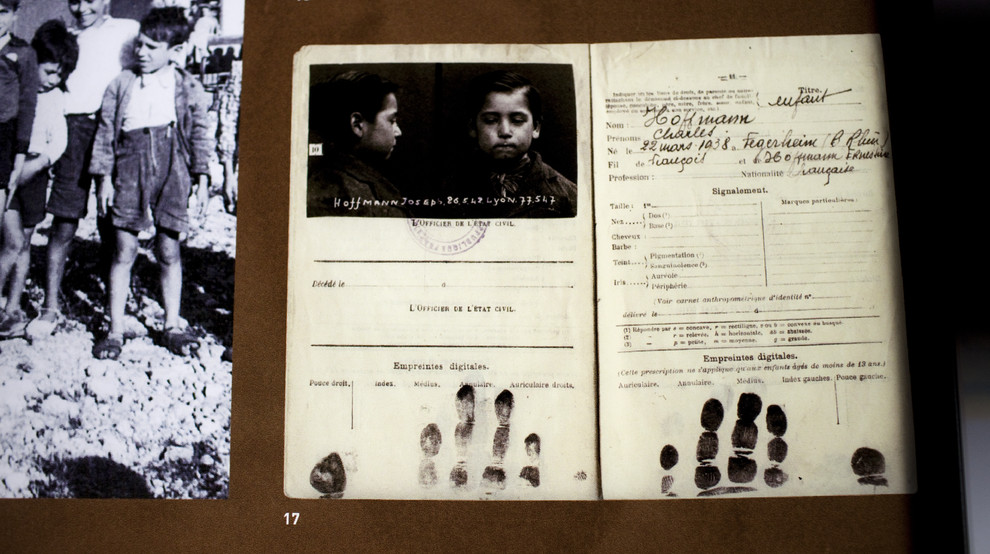

In 1942, under German pressure, the camp became a ‘Centre national de rassemblement des Israélites’ – a ‘sorting centre’ for Jews who were then sent on to the death camps such as Auschwitz, via Drancy. Two thousand five hundred and fifty one Jews are recorded as having been deported from Rivesaltes – four hundred of them were children.

Today a museum stands on the site, a silent witness to man’s inhumanity to man.

The History of the Memorial Museum

The first symbolic stone for the Rivesaltes camp memorial was placed by Christian Bourquin and Georges Freche in 2007 as they recalled the events which lead to the future project becoming a reality on the 42 hectares of land which now belonged to the department.

In 1998, Christian Bourquin refused to allow the demolition of the ruins of the camp barracks and the idea of a memorial was born. Many different peoples and religions suffered there – who should the memorial honour? Jews, gypsies, Spanish refugees, French Algerians, homosexuals…..even Germans imprisoned there after the liberation….?

It was finally decided by a ‘jury’ led by French architect and designer Rudy Ricciotti that It’s role should be to “account for the history of internment in France during the second world war, the camp from 1930 to present times, and the help and assistance given” The project was directed by Denis Peschanski, specialist in the terrible history of the camps in France during the second world war. Housed in a unique building, the museum earned its architect, Rudy Ricciotti, the Equerre d’Argent prize.

The one stumbling block which left a bitter taste in the mouths of all concerned was the high price that the department had to pay to the state for the land, instead of the hoped-for symbolic sum of money for something that concerns all humanity.

The Memorial Museum today

The 4,000-square-meter award winning building is made up of a long single-story sunken construction in concrete, monolith style, broken up by narrow patios. Inside, the only view is of the sky, visible through a few roof windows and the patios.

The permanent exhibition in the main gallery consists of a 30-meter-long interactive table featuring videos, interviews, maps, documents and objects related to Camp Joffre and other internment camps in France, personal stories of internees, and archive videos.

Outside, the desolate, abandoned barracks and ruins of the former camp emphasise the stark reality represented within the Memorial museum.

Described as ‘un musée de la grandeur de l’homme libre, pour un mémorial non de la défaite mais du combat, pour un musée de l’homme digne et debout’ (A museum to show how great is the free man, a memorial of combat, not of defeat, a museum showing man dignified and standing tall), you will not come away unmoved.

Check out their website www.memorialcamprivesaltes.eu or visit their Facebook page for temporary exhibitions, film screenings, concerts, lectures, and live performances taking place in the museum’s 145-seat cinema/auditorium throughout the year.

Visit this page for more about the history of the camp at Rivesaltes

Les Couleurs de l’Exil – Exhibition of work by Josep Bartoli

If he had not left behind him a few drawings, a few caricatures of his horrific stay in the French concentration camps, Civil War refugee Josep Bartoli (1910-1995) would have remained just another anonymous fighter among thousands of other nameless, faceless men who sacrificed their lives in the name of freedom.

In 1939 he crossed into France, and was incarcerated in a series of internment camps, including Bram, Argelès-sur-Mer and Le Barcarès, and Rivesaltes, where he drew the hell of life in the internment camps.

Escaping deportation to Dachau in 39, he settled first in Mexico, where he started painting in colour for the first time, influenced by his lover, famous artist Frida Kahlo, then in the United states where he became an illustrator for the American and French press.

He never set foot in Spain again until after Franco’s death, nearly forty years after his exile to Mexico.

Josep Bartoli died in New York in 1995 at the age of 85. In September 2019. His descendants bequeathed 270 of his works, drawings, paintings and collages

to the Rivesaltes Memorial.

Josep is a 74-minute animated film inspired by the life and work of this anti-Franco fighter and cartoonist.

Synopsis

February 1939. Completely overwhelmed by the flood of Republicans fleeing Franco’s dictatorship, the French government imprisons these Spaniards in concentration camps where many of them will perish from lack of care and food.

In one of these camps, two men, separated by barbed wire, became friends. One is a gendarme, the other is Josep Bartolí (Barcelona 1910 – New York 1995).

Aurel realised that this drawing could only be the work of a brilliant draftsman, and was amazed to discover the talent was replicated on on every page.

The rich political illustrations overflowed with detail and poignant meaning; criticising power, the state, religion, the cowardice of international leaders.

The force of Bartolí’s pencil struck a serious blow and pushed Aurel to bear witness to the horrific events, so little known from recent history.

rent/buy the film, with English subtitles, by subscribing to BFI Player.

WOW!!

[…] http://anglophone-direct.com/rivesaltes-memorial-museum/ […]