Perpignan: a gateway to freedom (and butter on your bottom!)

Historic Perpignan, colourful mix of old and new, chic and shabby, trendy boutiques, narrow, cobbled streets and small intimate bistros, owes much of its heritage and cultural development to the kings of Majorca, whose palace still dominates the town.

Jaume I, King of Aragon, Count of Barcelona, was justifiably known as James the Builder. His reign was a period of peace, prosperity and tolerance for Perpignan. Politics, commerce, religion, art all flourished. Different religions, colour and creed lived side by side.

Today, the streets are full of tourists, artists, photographers, smart businessmen and women, but just 80 years ago, the town was less of a culture hotspot and more of a gateway to freedom.

For many escapees and evaders, the town was one of the final stepping stones before embarking on the start of a difficult journey, across treacherous, snow topped mountains, dodging German patrols.

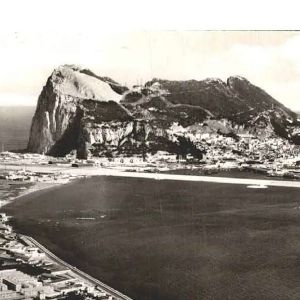

Their goal? To reach neutral Spain and ultimately Gibraltar, Britain and the rest of the free world. Resistance groups and escape committees provided guides at great risk to themselves.

From the opposite direction came those from that free world, wishing to take a more active role in the clandestine struggle against the Nazis, and those fleeing persecution in Franco’s Spain.

Once over the Pyrenees, it was usually possible to find help from the British consulate and reach Gibraltar, and on to Britain: sometimes by sea and sometimes by air.

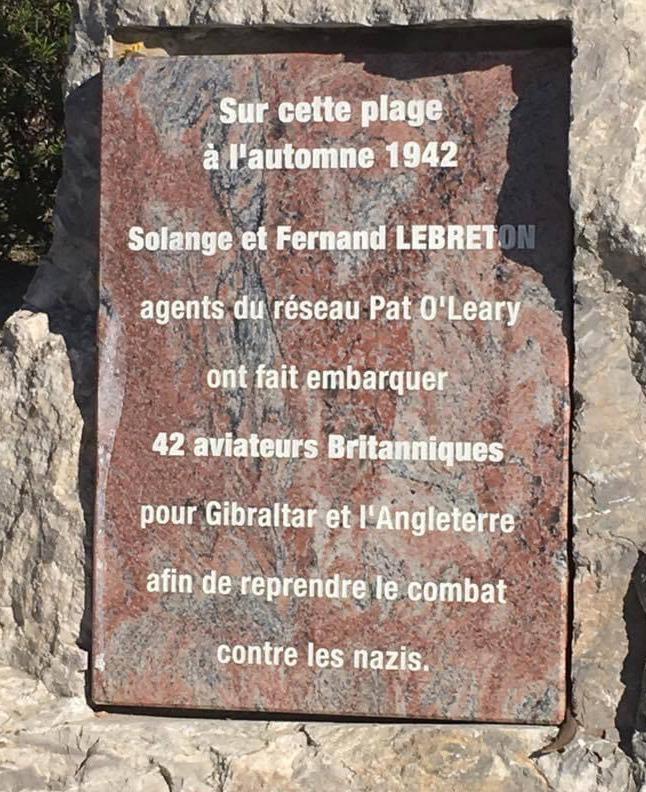

Perpignan’s position between Med and mountain also meant that British navy vessels could come in to shore at Argelès-sur-Mer, Canet, Banyuls-sur-Mer and Cerbère and reach Gibraltar directly by sea, avoiding the possibility of being picked up by the Spanish.

Perpignan therefore was a pivotal location in supporting the British and Allied war effort.

One of the largest and most successful sea escapes was ‘Operation Rosalind’. In 1941 at Canet-Plage, forty escapees waded into the sea every night for a week, waiting in vain for the flashing light from the rescue boat sent from Gibraltar.

Until Pat O’Leary, real name Dr. Albert Gursehzad, head of the successful escape and evasion route, the ‘Pat Line’, radioed London with the message “Pas plus de bateau que de beurre au cul!” (There’s no more a boat here than butter on my arse!).

The rather rude message produced results and they were picked up 2 nights later.