The Pat Line

Previously in P-O Life, we told the story of Belgian heroine, Andreè de Jongh, how she helped around 400 allied escapers and evaders to cross over the border to Spain in the northern Pyrenees.

In fact, there was a busier and even more successful escape route closer to home here in the P-O.

This route became known as the Pat Line, named after the man who got it up and running as a reliable escape route for as many as 600 escapers and evaders.

Amongst these was Airey Neave, former Conservative MP, later to be murdered by the I.R.A. at Westminster, who escaped from Colditz, and stayed in a safe house in Port Vendres.

THE MAIN PLAYERS

The story of this route is as fascinating as it is amazing, but for this part I will concentrate on the main players. Pat O’Leary, real name, Albert Guerisse.

Guerisse was a Belgian, serving as a medical officer in the Cavalry regiment, who escaped the invading Germans to the British shores through Dunkirk. He was soon recruited as a Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, working on hazardous and dangerous missions aiding and escorting agents to French soil through Vichy defences and patrols on small vessels, while the larger ship waited in the distance in the relative safety of darkness.

It was on one of these missions, Guerisse’s career took a surprising turn. On the night of 25th April 1941, he was en route to recruit agents for S.O.E. (Special Operations Executive) in the fishing village of Collioure when his boat sank and he had to swim ashore.

He was captured, unconscious, after being washed up on a beach at Collioure.

He claimed he was Canadian to his Vichy captors, to explain his poor English accent and his French spoken in a non French accent. He was also aware he had a family he had to protect in Belgium. He took on the name of a former military colleague, Pat O’Leary.

He was taken to St Hippolyte Fort near Nimes where he met up with other interned officers, including fellow S.O.E. man, Ian Garrow. Garrow managed to get Guerisse released and took him to Marseilles. Here he was introduced to the work of helping escapers and evaders and was introduced to Nancy Wake, British agent and leading figure in the maquis, and went on to form the Pat Line.

Guerisse was expecting this work to be temporary until he could be collected by the British off shore to continue his work with S.O.E. This was the plan until Garrow was captured in October 1941 and O’Leary, as he was now known, took over the escape line and organized it into an effective route.

O’Leary smuggled a German uniform into Mauzac Concentration Camp, in the Haute Garonne region, and in December 1942, Garrow escaped and was sent back to London to continue his work there.

O’Leary teamed up with the Reverend Donald Caskie who fled his Church of Scotland church in Paris just as the nazi’s arrived. He was not afraid to air his anti nazi views from the pulpit and this put him on their radar.

THE SEAMAN’S MISSION

He arrived in Marseilles and took over the Seaman’s Mission there. Number 46 Rue de Forbin soon became the biggest “safe house” in France, and probably the worst kept secret. It was common to see British officers strolling on the streets of Marseilles, as they were often given “officers parole” from their prison in Fort St Jean, a 17th century fort built by Louis XIV at the entrance of the port in the old town so this helped in keeping the “secret” safe for a while.

Food and clothing would be left in the doorways, there were often anonymous phone calls warning of raids by the Vichy police. Caskie would take the uniforms in large sacks at night and drop them into the sea at the old port.

The Seaman’s Mission was closely connected to the main “safe house” which was the doctor’s surgery belonging to Dr George Rodocanachi (Rodo), who with the help of his wife, Fanny, helped not only allied escapers and evaders but up to 2000 Jews. Rodo, a Greek, born in Liverpool, was a veteran of WWI and had received the Croix de Guerre as well as the Legion d’Honneur. His surgery became the meeting point for the escapers.

SAFE HOUSES

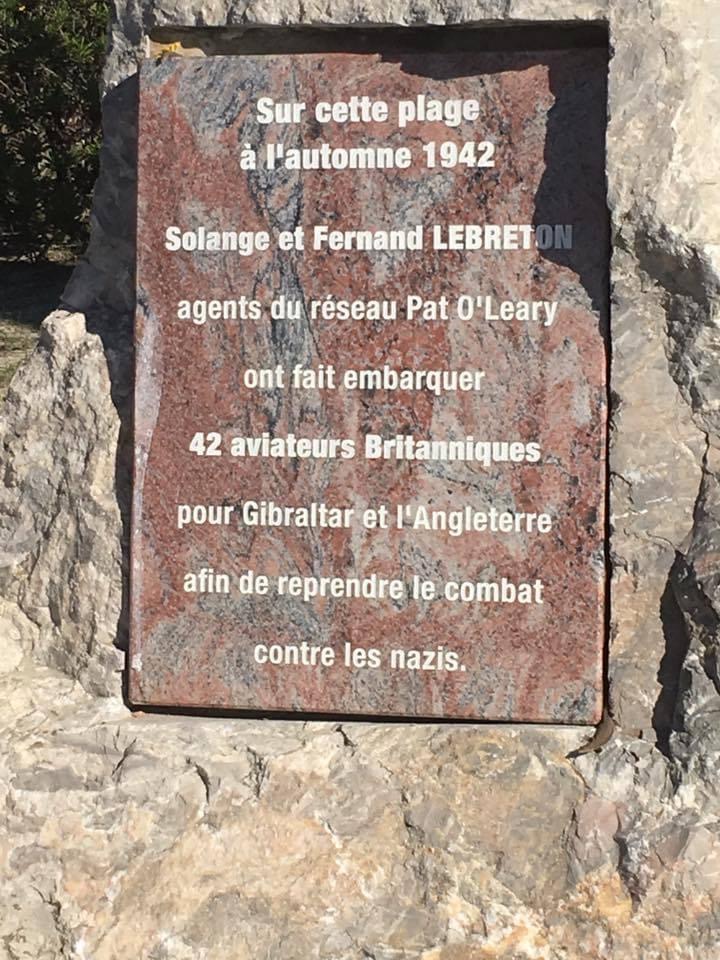

Escapers were generally sent down a system of “safe houses” in Narbonne, Perpignan, and stayed close to the border in small villages such as Port Vendres to await their, mainly Spanish, guides who took them over small tracks such as the Col de Banyuls, where there is a memorial to these brave men and women.

Some were taken away by ships and submarines that would wait off the beach at Canet. Most however, crossed the Pyrenees and were taken to Figueres where Spanish railworkers would help them get to Barcelona and the safety of the British Consulate

.In January 1943, the line was infiltrated by French double agent Roger Le Neveu. O’Leary was arrested by Gestapo in Toulouse in March of that year.

The British were warned of the arrest and infiltration by a young agent, Fabien de Cortes, who had escaped from the train he and O’Leary were being transported on.

Although tortured horrendously by his Gestapo captors, and sent to various concentration camps O’Leary gave nothing to them.

At Natzwieler Concentration Camp he witnessed the death of female S.O.E. agents, Andreè Burrel, Vera Leigh, Diana Rowden and Sonja Olshanezky and with fellow S.O.E. agent, Brian Stonehouse was able to testify to their fate, the only eye witness evidence preventing them from being lost forever in the nazi’s Night and Fog programme.

He was sentenced to death in Dachau but fortunately the SS guards surrendered before the sentence was carried out.

The line was taken over by Marie Dissard, who helped 110 to use the line to escape.

She would travel north and, like de Jongh for the Comet Line, she would escort them down. They would be kept in safe houses in Toulouse until she could escort them and hand them over to their guides across the Pyrenees.

Unfortunately one of the Pyrenees guides was captured in Perpignan in January 1944 and her name was in his notebook. Tipped off that the Germans were on their way she went underground in Toulouse and stayed there until the Ville Rose was liberated by allied soldiers.

It is unclear when the Pat Line closed, there are some stories that it continued until the end of the war but it is doubtful it continued after Dissard had to disappear.

BETRAYED

Escapers and evaders were finding it more and more difficult to get through to Spain as the Germans became more efficient at breaking and infiltrating the lines with the help of alleged British traitors like Harold “Paul” Cole a former courier of “packages” in the Lille area, until he was accused of embezzling funds for the line sent from London.

After being confronted by O’Leary he confessed all and escaped his fate through a small window. He was arrested by Gestapo in 1941 and soon started to give them all they wanted. It is believed he betrayed up to 150 men including Garrow and Guerisse. He became wanted as the Worst Traitor of the War.

Other routes were sought by S.O.E. including elaborate plans to get people across by boat from the Brittany coast but most attempts proved futile. Most escapers and evaders were instructed by the British to gather at a camp in Freteval Forest south of Paris and await extraction. This is a story in itself and one that ended successfully thanks to the sheer determination and bloody mindedness of Airey Neave just after the liberation of Paris.

What was the fate of the main players of the Pat Line?

Albert Guerissse himself was awarded the George Cross and 34 other decorations from various countries. He rejoined the Belgian army and served in Korea before retiring as a Major General. He died in Belgium 26 March 1989 aged 77.

Ian Garrow, died in Scotland in 1976 after a distinguished war career with S.O.E. and MI9.

Dr George Rodocanachi was arrested by six Gestapo officers in February 1943 and while in prison he continued to work as a doctor for fellow inmates. In January 1944 he was sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp in Germany, where he died in the Spring of that year.

Donald Caskie was sentenced to death by firing squad but after speaking with a German pastor, had his sentence commuted, and spent the rest of the war as a POW. He returned to Scotland in 1951 and was awarded the OBE as well as receiving honours from the French government. He wrote an autobiography about his exploits in a book The Tartan Pimpernel and the church he preached in, The Scots Kirk in Paris, was rebuilt in 1990 with proceeds from the book going towards the funding. He died in Greenock in 1983.

Harold Cole was hunted by both the French and MI9 but despite being captured and imprisoned in Paris, he escaped in November 1945. The French police found him two months later hiding at a bar in the Rue de Grenelle and shot him. He was buried, unmarked in a paupers grave in Paris.

This story is far too complicated and interesting to compact into such a small space and there were many great stories of heroism as well as some terrible tales of betrayal. Should you wish to learn more I can recommend the book Home Run; Escape from Nazi Europe by John Nichol and Tony Rennell

PR

FIND OUT WHAT HAPPENED NEXT

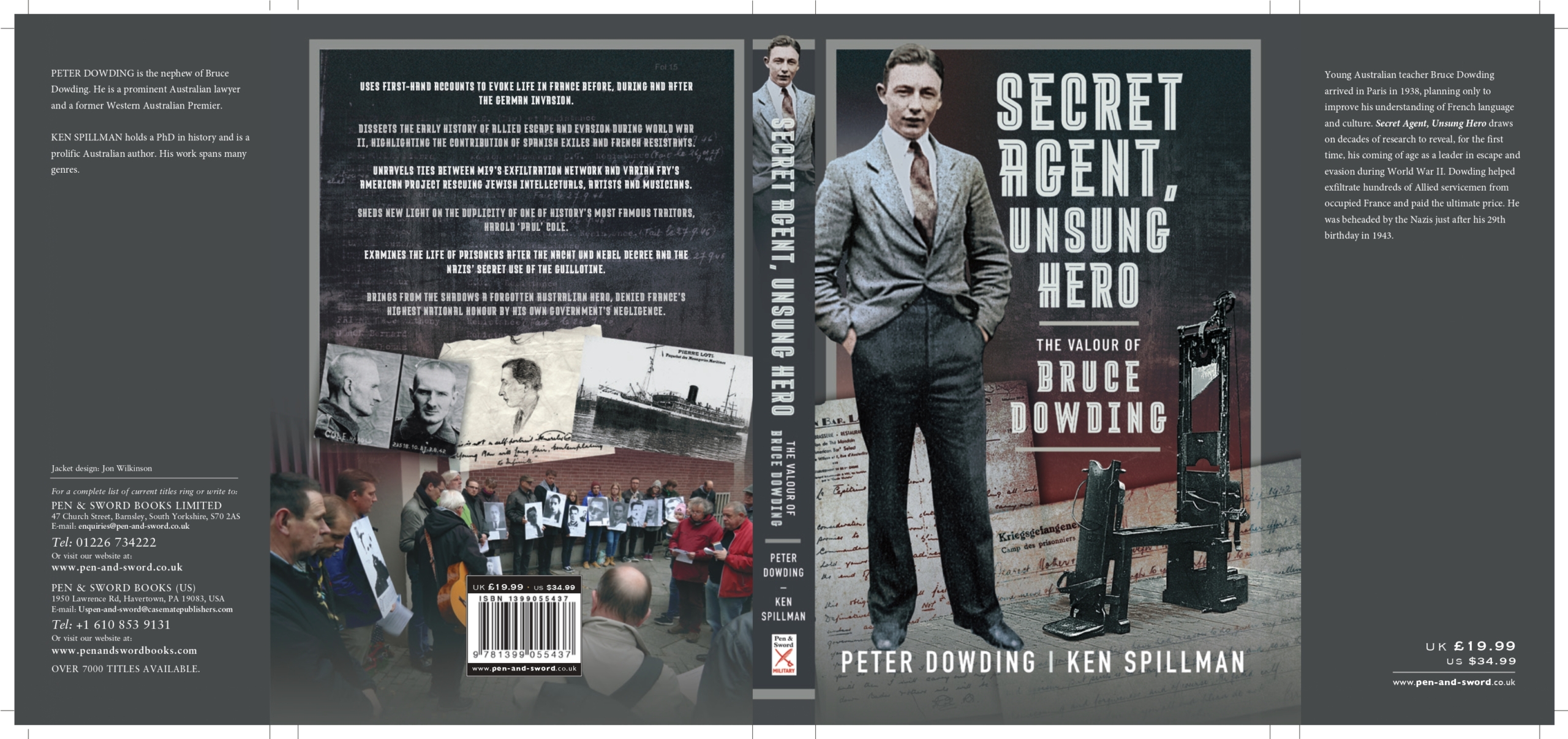

WORTH THE READ….Secret Agent, Unsung Hero

You may remember running an article about my Uncle Bruce Dowding who worked in the PAT line , in Perpignan at the Hotel de la loge, until he went to take over in Northern France and was later executed by the Germans.

If any one can help with the history of his friend Paulette Gastou whose family owned the hotel I would appreciate it

Hello Peter. I was at a symposium for Passeurs & chemin de la Liberte escapers in Oct in St Gaudens. I made contact with someone who works at the Resistance museum in Toulouse and other French historians who might have more information about Paulette Gastou. I am happy to make inquiries on your behalf. Best regards, Richard.

There is a book that includes an account of being an « evading » airman, Waves at my Wingtips, lent my copy to Norman from Trompettes Hautes and unfortunately he died . The author had flown flying boats before he was shot down. His personal account of the strategies used by his guides is fascinating. I was astonished by the courage of his guides’ some quite young.