by Ted Hiscock

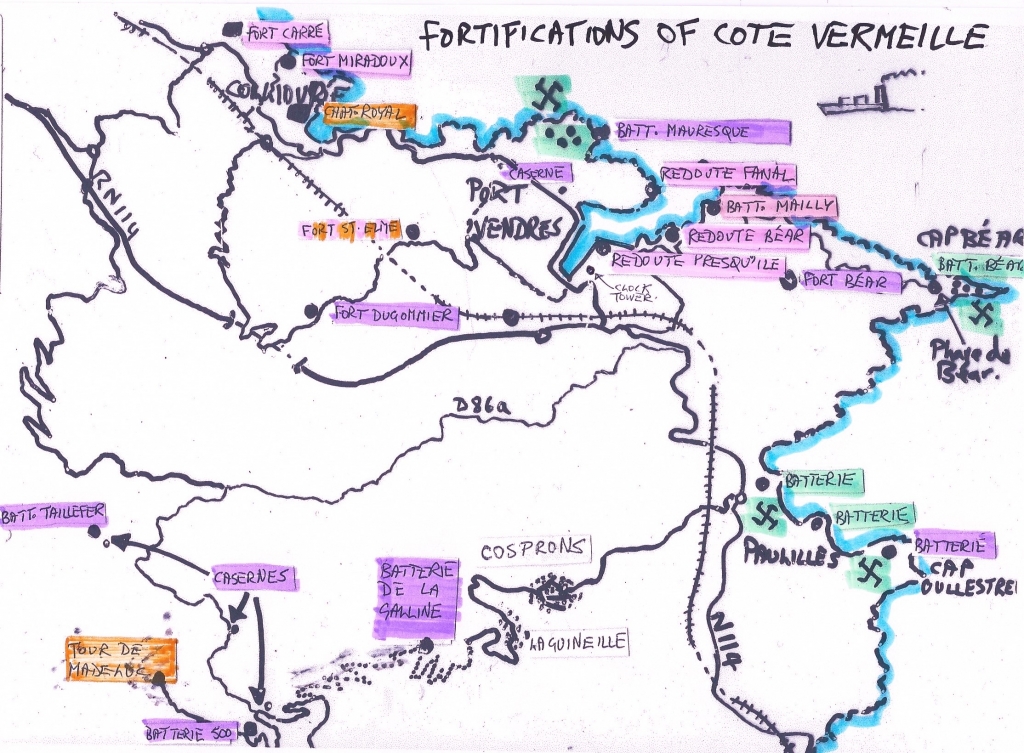

A simplification of the convoluted military history of the Cote Vermeille

Following the absorption of the Kingdom of Majorca into Aragona in 1276, for many hundreds of years, the department of Pyrenées-Orientales was under Spanish rule and during the 15th century, fortresses like Salses and Castell de Bellaguarda at El Pertús were built to keep the French north of the Corbieres.

In 1659, the Treaty of the Pyrenees was supposed to have settled the arguments once and for all between the two nations and defined the frontier along the current line.

However, incursions continued for years until Louis XIV’s brilliant engineer, Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707), fortified and built new and better forts throughout the region, in particular in the exposed and vulnerable frontier villages.

This was not limited to Roussillon for Vauban was famous for installing fortifications throughout France.

Within this newly annexed Roussillon, Vauban fortified a number of villages including Mont-Louis (1681), Villefranche-de-Conflent (1707) and Prats-de-Mollo (1679) at the heads of the Conflent and Vallespir valleys.

In 1678, following the Treaty of 1659, he also set about strengthening the newly acquired Bellegarde at Le Perthus. This clearly unnerved the Spanish, who retaliated by enlarging the magnificent Castell de Sant Ferran (1753) to the east of Figueres, (today, Spain’s largest fortress and well worth a visit).

Even after this politically agreed frontier, battles continued for years to come and the Cote Vermeille became a military quagmire between the two nations.

Not only were there land attacks, but some villages were vulnerable from the sea. In particular Collioure and Port Vendres, (the latter with its natural deep harbour) a mere 20km from the new Spanish frontier, were considered by Vauban to be particularly at risk.

In 1669 he visited Collioure and left vague instructions for the town’s fortifications to be enhanced.

The Chateau Royal was to be linked by a high wall to the newly constructed Fort de Miradoux to the north of the town with a satellite Fort Carré (ultimately built 1725).

However, he wrote that Collioure was not worth improving at the time, and in 1679 he even suggested razing it to the ground and starting again! If he had, I wonder if it would have been the charming place we know today.

Vauban’s particular interest was for Port Vendres and its magnificent naturally deep harbour which he considered vulnerable but extremely useful to moor a French fleet. He set about strengthening its defences on a grand scale.

Port Vendres and Collioure face the Mediterranean to the North-East but otherwise sit in a horse-shoe of mountains on all other flanks. With a very chequered history of invasion over the centuries, Vauban recognised the need to protect this underbelly of France.

Part of his grand plan consisted of making considerable extensions and improvements to 14th century Fort St. Elme sitting at 170m on the col between Collioure and Port Vendres.

Fort St. Elme was strategically positioned with clear views of the sea, the Spanish coast, the Chateau Royal of Collioure and the natural harbour of Port Vendres with the two 14th century beacons of Madeloc and Massane, high above on ridges of the Albères. These were Vauban’s higher outer defences.

When he studied the natural harbour of Port Vendres, Vauban made more specific plans to counter any sea attacks on the fleet.

In 1678, he designed a ring of inner defences around it by constructing small immediate fortresses (Redoutes) on either side of the harbour mouth. To the North-West was the Redoute Fanal and on the South-East, the Redoute Béar.

Both exist today, with Fanal, being in poor condition and Béar being seriously damaged by the departing German army in 1944 but now thankfully rebuilt to house the museum of Sidi Farruch, a commemoration of 100 years of French rule in Algeria.

Vauban placed a third inner fortress, the Redoute de la Presqu’Ile, on the promontory where today container ships unload North African fruit at the Port de Commerce. The only remnant of this installation is the rebuilt clock tower moved to its present position behind the Douane offices on the south side of the port.

During the reign of Louis XVI, le Compte de Mailly was appointed Lieutenant Général of the province and in 1775 he continued with Vauban’s initial defences by building an extra fortress close to the Redoute Béar, which was named after him. Sadly, this too became a victim of the retreating German occupational force in 1944.

During the French Revolution, the War of the Pyrenées broke out in 1793, when a Spanish force invaded Roussillon occupying much of the region. Port Vendres (including the fortresses of Fanal, Béar and St. Elme) and Collioure (Chateau Royal) were both occupied.

A deciding bloody battle took place at Le Boulou in April 1794 when the French Revolutionary army, under the command of Guatemalan born General Jean Dugommier, sent the Spaniards packing.

The bulk of the retreating Spanish army slipped back through the pass of Maureillas to the Fortress of Sant Feran at Figueres.

A little later, Dugommier was seriously wounded whilst trying to retake St. Elme above Collioure but continued his attack forcing all Spanish troops to temporarily re-muster in the Chateau Royal of Collioure – but they were no match for the superior French forces. Some escaped by sea and others surrendered.

Despite the main Spanish army being routed by Dugommier’s forces, a small group did hold out at Bellegarde above Le Perthus for about 5 months until starvation led to capitulation.

Dugommier pursued the Spaniards back into their own land but both he and the Spanish general died in the subsequent battles around Figueres.

During the first 75 years of the 19th century, turmoil between the two countries continued.

Firstly, Napoleon placed his older brother Joseph as King of Spain in 1808. Although trying to buy support by granting Catalunya independent republic status and encouraging them to use the Catalan language, it was seen as a patronising gesture by the Catalans, who refused to be subservient to either French or Castellan rule.

Later in the century, industrialisation, social unrest and staunch Catalan nationalism in Barcelona led to the advent of political factions which must have made the French nervous of their Iberian neighbours once more.

For this and other reasons, a number of increased defences were planned throughout the Cote Vermeille. A new fort, at first called Redoute Palat at 223m. but later renamed after Dugommier (1844-52), was built close to Fort St. Elme on the col between Port Vendres and Collioure.

La Mauresque (1846-50) was built on the headland to the North-West of Port Vendres, on the site of an ancient fortress jutting into the sea and a square fort was placed on the headland of Cap Oullestrell (1846), south of the beaches of Paulilles.

Later, during the second half of the 19th century, further military installations were constructed.

Fort Béar (1877-80) on the top of the Béar peninsula, Fort de Galline (1885-6) perched at 260m on an outcrop above Cosprons, 2 Batteries, 500 and Taillefer (both at 500m.) with three substantial casernes (barracks) being strategically placed high under the Tour de Madeloc, where the soldiers were billeted.

![2014 : Redoute Mailly [Charles Rennie Mackintosh]](https://anglophone-direct.com/ap_img/PA161299-1024x768.jpg)

It was the occupation by the German 19th Army in the Second World War that led to their destruction between 1943-4.

The section of the German army that was stationed along this coast was part of the Sudwall (the 864km massive defences along the whole French Mediterranean coast to repel a possible allied invasion from the sea).

In Port Vendres concrete bunkers, gun emplacements, search lights and barracks were quickly and effectively installed throughout the headlands of La Mauresque, Mailly and Béar as well as the beaches of Paulilles. These extensive and substantial engineering works still remain 70 years later although decaying, act as a historic reminder of the horrors of modern warfare.

Today, there is a move to retain and restore many of these decaying historic monuments and to this end, volunteer groups have sprung up with government backing. As usual, lack of money is a problem but these pioneering groups have shown great enthusiasm and positive drive to restore the local heritage.

To enjoy a better understanding of these locations, follow ‘the walks of Ted & Kate Hiscock in the Region’ that take in some of these amazing military installations.

REFERENCES:

FORT DUGOMMIER DE COLLIOURE The Restoration of Fort Dugommier www.dugommier.com

LE PROJET DU FORT DE LA GALLINE www.Lefortdelagtalline.blogspot.co.uk

LE FORT MAILLY « LES CHANTIERS DE LA MEMOIRE » www.ouillade.eu/environement/port-vendres-le-fort-mailly-de-ses-cendres/69475

Excellent resumé, thank you!